Notebook: Three easier pieces

Pricing politics, Spain's cold war, and Italian conservatives live down to expectations

Listening to some Spaniards complain about the government’s emergency energy-saving plan, I was reminded of Jason Manford’s retort when a heckler told him the “worst pain ever” was a paper cut: “Have you ever been stabbed?”

In an initial round of preparations for Europe’s first winter since Russia invaded Ukraine, Spain’s centre-left cabinet decreed that air conditioning in non-residential buildings shouldn’t be set below 27 degrees Celsius. This applies everywhere except hospitals, schools, hairdressers, laundries, gyms and public transport. On top of that, lights in unoccupied businesses must be extinguished after 22:00.

It'll shock no one to learn that Spain – especially Andalusia and Murcia – get quite warm in the summer. Having the AC at 27 degrees will take the edge off 35-40 but it’ll be uncomfortable, and promenading past unlit shopfronts and public buildings on the way to pre-dinner drinks after ten will feel positively Calvinist.

On brand as always, Isabel Díaz Ayuso – the boosterish commerce-first governor of the Madrid region – has refused to comply and taken her fans in the opposition Partido Popular with her, denouncing the decree for causing “darkness, poverty, and sadness”. Sad face. Following her lead, other PP regional governments – most notably in Galicia – have called for the decree to be revoked and renegotiated. Already, the resistance has paid off. Teresa Ribera, the environment minister who drafted the law, now concedes that the AC can be set “around 25” rather than 27.

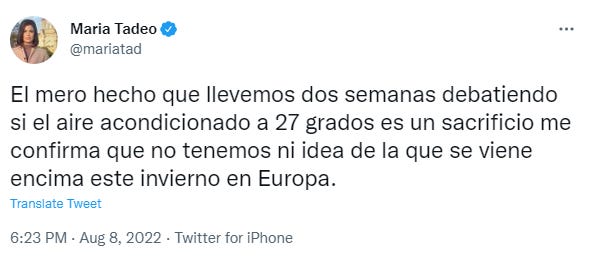

Opposition is understandable. The forecast for today and the coming month is - in the words of Mister Señor Love Daddy - “HOT!” and what is a balmy noche madrileña without up-lit monuments and shopfronts? But, as Bloomberg TV anchor Maria Tadeo rightly tweeted last week: “The mere fact that we have been debating for two weeks whether 27-degree air conditioning is a sacrifice confirms to me that we have no idea what is coming this winter in Europe”.

As long as the continental winter is not unusually cold, the EU continues to import record volumes of liquified natural gas (and cargoes aren’t diverted to Asia if its winter is atypically cold), and Russia meets expectations to double its reduced pipeline flows by October, then we should scrape by without mandatory rationing. That’s a lot of conditionals. And they only work if the gas price stays dissuasively close to its all-time highs of around €200 per megawatt hour (equal to 330 homes’ electricity consumption during one hour).

So far, so horrible. Yet there are quite a few things that could make things worse – chief of which is a Russian decision to respond to a major military setback with a retaliatory gas embargo. If this happens, industrial shutdowns will be required to ensure continued supply to households and critical services. Those businesses and their workers will get pandemic-style compensation but energy prices will have to go even higher to limit demand while the poorest households are rescued. This is going to hurt a lot more than a sweaty summer but there’s a war on, you know.

A duet of fiddling Neros

With six weeks to go until Italian election day, Giorgia Meloni – who has finally declared she’s up to being prime minister – is getting lots of international attention. Everyone wants to know who the real leader of Fratelli d’Italia is. Is she the evolving stateswoman who broke with her right-wing allies to pledge unconditional support for Ukraine or the nativist demagogue feeding applause lines to Vox activists in Marbella? Does she still want to amend the constitution to remove “the constraints deriving from EU legislation and international obligations”? Will she appoint a market-whisperer as finance minister?

In reverse order, the answer to those is: yes – with names like Claudio Descalzi and Domenico Siniscalco1 in the frame, no – since that was futile oppositionism and she doesn’t want to waste time in government, and both – she has grown up a lot since office beckoned but she is also a traditionalist conservative keen to block the emergence of a new force to her right.

The problem with the focus on Meloni is that her government’s performance is not entirely up to her. Not only does she lead a party with a fascist-adjacent cadre but any cabinet she heads will be composed of a three-party alliance. And, at the top of those two other parties are resentful older men – Matteo Salvini (Lega) and Silvio Berlusconi (Forza Italia) – who take her as seriously as they do hard budget restraints.

Both laud the record of the outgoing Mario Draghi administration they propped up because they know that’s what their entrepreneurial bases want to hear. But their support isn’t even permatan-deep. Both think compliance with the terms of the EU’s €200-billion post-pandemic recovery programme for Italy is a matter of “respecting the times and deadlines”. In other words, once a quarter they will check the boxes on conditional reforms but will have no intention of implementing them. In fact, on the big issues, their stated intention is to make matters worse.

Fundamental to Italy’s medium-term programme is a reduction in retirement spending but Berlusconi’s core offer is a €33-billion annual pension increase. As for Salvini, he’d be up for a massive pension increase but that’s all a bit 2018 when he did God’s work and paid for northern male state employees to head to the beach early. No, this time, the Capitano wants his 15% “flat tax”, which will be phased in over two years at a cost of €15 billion – or €50 billion as it’s known on Planet Earth. If he were even remotely in earnest, there’s a lot to be said for an Italian flat tax or something like it. The country needs a super-simple, hard-to-dodge tax code with its 720 loopholes worth 16% of GDP eliminated and revenues collected. But Salvini is as serious about this as Berlusconi is about his €1,000 minimum monthly pension.

What their campaigns do tell you – like Team Ayuso in Spain’s cold war – is that the right-wing alliance that is poised to take office in October has no idea what’s coming. Berlusconi has learned nothing from his 2008-11 experience in government and Salvini even less from 2018-19. Even if Meloni 2.0 is for real – telling the leadership of the right that it “can't play with fire. The situation is delicate … Italy risks default if we make a mistake … Personally, I will not allow it” – her coalition partners aren’t.

The price is wrong

Like anyone who writes about British politics, I admire Janan Ganesh’s elegant prose style so it gives me only a little pleasure to challenge his claim that a Conservative victory at the next British election is “underpriced”.

Claims of political under- and over-pricing are a bugbear of mine. What people usually mean is that they have a feeling that a common assumption (common to people they know, that is) may be wrong. As often as not, their contrarian take is based on the last political shock: the Brexit referendum, the election of Donald Trump or Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s never the shocks that didn’t happen: the euro having “10 days at most” to live in 2011, Marine Le Pen’s 2017 election and triumphant 2022 re-election, and Trump’s “frankly we did win this” re-election in 2020.

If you don’t have clients literally trying to price political risk, you can make these throwaway assertions. Throughout 2019, I was asked to assess the risk of a “no-deal Brexit” (remember when that was a thing?) and whether I was more or less confident following the latest British public tanty. I never believed it would happen so, even after brinksmen Dominic Cummings and David Frost assumed power that July and hired Boris Johnson as their spokesman, I stuck with “10% at most”. The political incentives only ever pointed one way.

At a pitch to an investment bank that autumn, I was told William Hague had been in that very day and assigned 40% risk to a no-deal Brexit. Should I rethink my 10%? After all, he’d been Conservative leader and foreign secretary. Nope - even 10% was generous for a risk that wasn’t going to materialise. I let the potential clients - and I’ll let you - into a little secret: politicians are great sources of information but their risk assessment is terrible. An hour-long conversation with a minister, committee chair or MP during which they make a 99% case for an outcome will invariably end with: “I’d say it’s 50/50”.

So, whenever someone tells me a political contingency is underpriced, I ask them what the price is. Unless they’re market professionals, they never know. For example, has anyone told you recently that the US Democrats hanging onto the Senate in November is underpriced? Well, it’s priced at 55%. A second Trump presidency in 2024? He’s at 32% to Joe Biden’s 13%. Political pricing can’t be guessed. It has to be seen and, for that, you have to go to the Betfair or Smarkets exchanges or - for the Americas - the PredictIt, Polymarket and FTX prediction markets. This is what Smarkets is telling us today about the likely outcome of the next British election.

Is that under- or over-priced? Bear in mind that Rishi Sunak is still in the race so you have to add those two probabilities together until he isn’t. I think Liz Truss is overpriced relative to Keir Starmer. Why? Because the Labour party doesn’t need to win the next election; the Tories just have to lose it, and that is easily done. Beyond the rapidly disappearing Democratic Unionist Party, the Tories have no one else to prop them up by coalition or confidence and supply. By contrast, even if Labour fails to win an overall majority in the House of Commons, which is almost certain due to its structural weakness in Scotland, it can rely on every other party to keep it in office. The Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party will exact concessions but they would never be forgiven for allowing the Tories back into power. This means Labour will form the next government even if it trails the Tories by two points at the next election.

Don’t believe me? Take the late-July YouGov poll showing Labour’s lead down to just one point and drop the numbers into the Electoral Calculus seat-projection tool (making sure to include the Scotland prediction) and this is what you get.

To govern, a prime minister needs support from 326 MPs (320 once the speakers and Sinn Féin boycotters are stripped out). Starmer can find that reserve to top up his 280; Truss can’t. But isn’t Electoral Calculus based on a uniform national swing and what about recent Tory outperformance in traditional (“red wall”) Labour seats? Here too we have data. Redfield and Wilton Strategies poll a representative sample of 40 of these seats where the Tories beat Labour in 2019 by 47% to 38%. Last week’s poll put Labour at 48% and the Conservative at 33%.

The odds still look generous to me.

Descalzi is the CEO of Italian multinational oil and gas supermajor Eni S.p.A. and Siniscalco is vice chairman of Morgan Stanley Europe, was director general of Italian Treasury (2001-04) and briefly finance minister under Silvio Berlusconi (2004-05).

..... and their spokesman Boris Johnson. - nice!