Erik Nielsen1’s Sunday Wrap – this time resisting some of the more apocalyptic commentaries on Italian debt sustainability – was typically elegant and thought-provoking. It was also, in my view, excessively optimistic.

This is all about politics2. Italy is a rich country and its government could easily service and reduce its debt, especially if it lifted its trend growth rate and collected the taxes it imposed. Political inertia or active pandering always gets in the way and Italy has been on holiday from politics-as-usual for the past three years. Yet, not even Roman holidays last forever.

In the same way that the various Doctor Dooms3 saw nothing but perpetual crisis from inside the 2007-2012 crisis, I think Nielsen is extrapolating from three years of political self-repression, a budgetary freedom pass, north-to-south fiscal transfers, and a real or perceived “Lagarde Put”4 for Italian government bonds (BTPs).

The good

Granted, at 9%, interest costs as a share of fiscal revenue are well below the pre-crisis trend and entirely manageable.

Yes (crucially), half the public sector’s outstanding debt is domestically held and more than half of the remaining half sits on the balance sheet of the Eurosystem (care of the Bank of Italy). This means the debt is less vulnerable to speculative selling and governments have a stronger-than-normal incentive to avoid default.

Admittedly, Italy is still entitled to draw down €125 billion from the pandemic-era recovery and resilience fund (RRF) over the coming three years. And, finally, Giorgia Meloni has proved to be as west-facing and fiscally conservative as prime minister as she sounded in opposition … the final few months of it, anyway.

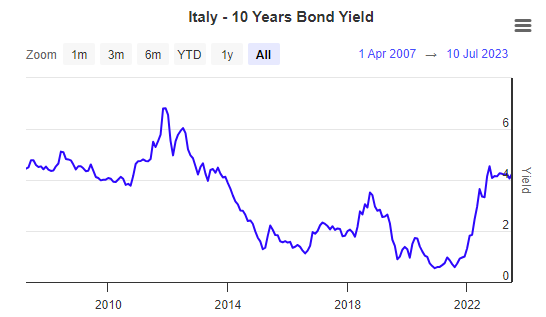

And, to Nielsen’s pluses, I’d add two more. First, the government’s ten-year borrowing rate may have surged from 1% to 4% over 18 months but, until now, new bonds have been issued at rates lower than those on the bonds they were replacing from a decade before.

Second, the next step in the European Central Bank’s counter-inflationary strategy relies on sustaining a restrictive monetary policy stance into 2024. Since that would be derailed by asymmetrical tightening of financial conditions in one big economy, the ECB has an even greater incentive to deploy its so-far-unused transmission protection instrument (TPI) to cap BTP yields as long as inflation is projected to stay above target.

The bad

However, this isn’t a discussion about the near-term but about a structural narrowing of the BTP-Bund spread. Structurally – that is to say, beyond the crisis-solidarity driven by Covid and compounded by the Ukraine war – the case for a capped 200-basis-point spread is harder to sustain.

For example, as Nielsen admits in the wrap, Meloni’s coalition partners are already lobbying for increased public spending in the run-up to elections to the European Parliament and to the Piedmont regional administration in June 2024. Ramming through a 2023 budget in the dying days of 2022 with a strong and recently won personal mandate was easy. Doing the same with the 2024 budget this autumn will be a lot harder as Matteo Salvini, Meloni’s embittered Lega rival, and a rudderless Forza Italia jostle for relevance. Next year’s budget-making for 2025 will be worse still.

In this respect, you can look at the €125 billion still due from the RRF and think of it as a fiscal glass two-thirds full. Or you can look at the political and administrative bottlenecks that mean only €67 billion has been drawn down so far, less than half of that spent, and another €19 billion delayed and speculate about what may happen between now and the RRF’s expiry at the end of 2026.

Already, Meloni is seeking a draw-down extension. Today, she benefits from goodwill for her support for Ukraine, for not being Salvini, and in recognition of her domination of the Italian right. To an extent, she could sustain this if she sees off Salvini next June, annexes Forza Italia, and the opposition begins a civil culture war. But the honeymoon will eventually sour and northern governments that have already ensured the hold-up of the latest €19-billion RRF tranche are sure to revolt against softening the conditions attached to transferring €125 billion to Rome. Even more so if, between now and 2026 and as the Ukraine war afterglow fades, Meloni advances her socially conservative agenda and her eurosceptical wing rediscovers its voice.

As for the Lagarde Put, that too will wither in line with underlying inflation. The ECB’s hawks never wanted to underwrite BTPs but they accepted the TPI as the price of getting a 400-bp-plus interest-rate cycle. They will reluctantly accept it as the price of keeping policy restrictive as they bear down on core-inflationary pressures. Once those are contained, the TPI is DOA.

Group chief economics advisor at UniCredit Bank.

I link to Nouriel Roubini, the original Doctor, but it could just as easily have been Paul Krugman, Wolfgang Münchau, or Ambrose Evans-Pritchard to name only three.

When Alan Greenspan headed the US Federal Reserve from 1987 until 2006, market commentators detected a pattern that the central bank would bail out shareholders with lower rates or liquidity injections every time equity values dropped sharply. This pattern of behaviour, which became known as the "Greenspan Put", was assigned to the ECB in its capping of Italian bond yields first under president Mario Draghi and then under Christine Lagarde.