Notebook: Phase Three

New world for ECB, old world for DUP

Even before carrying out the biggest single interest-rate rise in its history this week, the European Central Bank had already declared a “new phase” for its monetary policy.

Officially, the phase is characterised by an end to years of market-coddling with forward guidance1 and an accelerated return to policy neutrality – an interest rate consistent with stabilising inflation at the ECB’s 2% medium-term target while also closing the output gap2.

Unofficially, the new phase marks a seachange in policymakers’ thinking – a third regime of structurally higher inflation to succeed the mildly inflationary 1999-2011 and the 2012-2020 “lowflation” periods3.

With inflation over 9% and gas prices up 240% since January, it may appear obvious that the ECB has to raise interest rates quickly. However, monetary policy works with lags of at least 18 months, meaning that an interest-rate rise today won’t be fully felt in economic activity and prices until 2024. So, this rate rise (and the three or more that are sure to follow), will pass through to the economy after growth has slowed from 3% this year to 1% next, according to the ECB’s updated forecasts, and with the risk that the economy could even contract by 1% next year. Added to that, typically, central banks don’t raise rates to offset a supply shock – classically, a spike in oil prices – unless they believe the domestic economy is strong enough to embed those higher prices in inflation expectations, higher wages and profits.

Against this backdrop, the Wall Street Journal’s Jon Sindreu finds the ECB’s frontloading “incredibly baffling”. There are two reasons for this. The first is that, despite this week’s big move, the policy rate isn’t far from neutral and the ECB isn’t (yet) making a case for a restrictive policy to sweat inflation out of the system. The second is that the real significance of the new phase has been left unsaid. Survey-based inflation expectations are showing early signs of “de-anchoring” from the ECB’s target as high backward-looking inflation is factored into future plans. But, underlying all this is a belated recognition among dovish ECB officials that the repeated inflation surprises of the the past two years include a demand as well as a supply element.

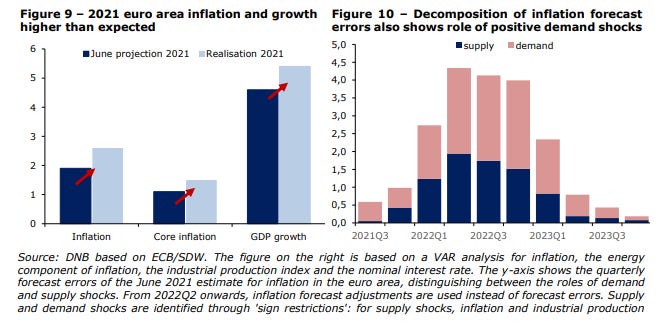

Research published in the spring by the Nederlandsche Bank concluded that the unexpected rise in inflation in the second half of 2021 was due to demand as well as supply shocks since the latter is typified by a combination of higher inflation and disappointing growth forecasts. Marco Hoeberichts and Annelie Petersen wrote: “The broadening of inflation suggests that demand shocks play a role since the more goods in the inflation basket show an increase in price, the more likely it is that this is driven by increased demand rather than supply problems for specific goods”.

Source: Inflation and monetary policy (DNB, 2022) by Marco Hoeberichts and Annelie Petersen (p.9)

This acknowledgement is especially important in the new phase as an accelerated green transition, permanently higher energy costs and consequent lost industrial capacity will entrench higher inflation. In the short term, euro area governments will be tempted to follow the lead set by Liz Truss’s new British government and throw borrowed money at the coming winter crisis. As Klaas Knot, the ECB governing council’s Dutch governor, warned on Friday: “With the tightening of monetary policy, European governments should be mindful not to implement generic fiscal support measures. Instead, targeted fiscal measures should focus on distributing support where needed most”. If euro area governments turn Trussista, higher ECB interest rates will be the least of their problems. I’m looking at you, Giorgia Meloni.

The gang that couldn’t shoot straight

If there’s one minor positive to come out of the looming winter crisis, it’s that Truss will shelve her plans to trigger Article 16 of the Northern Ireland protocol to the EU/UK withdrawal agreement. Starting a trade war with the EU and against the express wish of the White House just as Russia fully weaponises energy supply against Europe, and NATO returns from the dead is a step too far even for the chosen one of the European Research Group and her new ERG-approved secretary of state Chris Heaton-Harris.

Like night following day, their alternative to trade war – extended grace periods beyond mid-September for checks on goods moving between Northern Ireland and Great Britain – yet again puts the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in an awkward spot of its own making. Northern Ireland’s assembly and executive remain in suspense four months after an election topped by Sinn Féin because the DUP refuses to enter government until the protocol is overhauled.

Is there a political party in the developed world that is worse at politics than the DUP? Its leader Jeffrey Donaldson is patting himself on the back for restoring party approvals to 24%, according to a LucidTalk poll conducted on 12-15 August, by appealing to anti-protocol voters who had defected to the breakaway Traditional Unionist Voice.

Talk about missing the point. By campaigning for Brexit in 2016, the DUP turbocharged Irish unification. For the century of its existence, the island’s northern province of the UK has been majority Protestant and minority Catholic but, by the 2011 census, this had narrowed to 48.4% to 45.1%. The results of the 2021 census due in the autumn could even reveal a majority Catholic population.

Now, being from a Catholic tradition doesn’t necessarily make someone in favour of Irish unity and the same poll showed 48% wanting to stay in the UK and 41% preferring Ireland. However, Brexit and the DUP’s conservative positions on social issues have produced an unmistakeable trend: unification is now supported 57/35% by 18- to 24-year-olds and 48/42% by 25-44s. Around 35% of the province's population hold Irish passports and, with the lifting of pandemic restrictions this year, Northern Irish applications for Irish passports are running at 419 a day compared to 198 for the British blue-retro version.

Having expected a Sinn Féin politician to serve in the executive as deputy first minister for 17 years, the DUP’s refusal to consider swapping places if they lost the May election bolstered support for Sinn Féin. Donaldson reversed this position after the election but then suspended government formation until the protocol was scrapped or amended – a hiatus that is feediing non-unionist antagonism and increasing support both for Sinn Féin and the non-sectarian, europhile Alliance Party. There is also the little matter - always ignored on the British right - that a majority in the north supports the protocol. Depriving Michelle O’Neill, the first minister-elect, of a record of incumbency also robs her of facing the blame for policy errors.

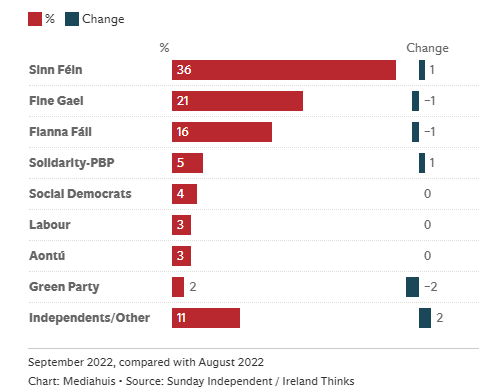

This is already political malpractice by the DUP but, given the state of politics in Dublin, it is suicidal. Sinn Féin is holding a consistent double-digit lead (see the latest Ireland Thinks poll below) over centre-right Fine Gael, and Mary Lou McDonald looks set to lead a government from 2025 that reunites the two long-divided strands of republicanism represented by Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil.

This is the DUP’s worst nightmare. Although it has detoxified at warp speed over the past ten years, Sinn Féin still carries stigma with moderate unionists. A government incorporating Fianna Fáil, Labour and the Social Democrats would ensure not just a rebranding of republicanism but the drafting of a carefully constructed and culturally sensitive roadmap to unity. Take a look at this early effort by Jim O’Callaghan, a prominent Fianna Fáil politician, and imagine what a combined government campaign and the full force of Irish professional diplomacy could do.

Bertie Ahern’s suggestion that a unification referendum should be held in 2028 to coincide with the 30th anniversay of the Good Friday Agreement has made a lot of sense to me since the day the former Fianna Fáil taoiseach said it. If anyone can deliver the century-old dream, it’ll be the DUP.

A strategy used by many central banks since the 2008 financial crisis to describe and predict the state of the economy and inflation and the expected path of interest rates.

An estimate of the difference between an economy’s actual output and its potential output (the rate of growth the economy can sustain without creating excess inflation - now estimated around 1.3-1.4% for the euro area).