Pick 'n' mix

How Macron lost the majority he wanted but won the majority he needs

“A political earthquake” … “gridlock” … “ungovernable France”.

Okay, it’s embarrassing that – having been re-elected to the French presidency only nine weeks ago – Emmanuel Macron went on to lose his overall majority in the national assembly. But, based on these reactions and the usual fact-lite commentary from academics-turned-trolls, anyone would think an ambitious reform programme had been derailed by an extremist wave.

In fact, while Macron may not have the majority he sought, he has the majority voters wanted and the one he needs to fulfil his one reform promise: an overhaul of France’s complex and costly pension system and an extension of the retirement age to 64-65.

Beyond that necessary but politically challenging reform, this new assembly – perfectly reflecting, as it does, the malcontented id of the French voter – provides a centrist-magpie president with a unique opportunity. It will require considerable political adroitness, but a second-term Macron could lean on the centre-right to add education and public-finance reform to pensions, on everything to the right of centre to address voters’ security demands, and on the centre-left and Greens for his environmental agenda. Having stolen his political clothes (and dignity), the least Macron could do is realise Manuel Valls’ left/right gauche républicaine vision with a majority the less fortunate former prime minister lacked.

A record of success for this second and final Macron term is crucial. These legislative elections have changed the battleground for the 2027 presidential run-off. For the first time, by winning 89 seats, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) has picked the lock on France’s two-round, first-past-the-post electoral system. It is now conceivable that Le Pen or, more likely, Marion Maréchal or Jordan Bardella, could secure a nativist, eurosceptical majority in 2027. Across the aisle, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI) has become the hegemonic force on the left and established the principle of “disobedience” of EU law in pursuit of its goals.

Both parties have bandwagons serviced and ready for the inevitable protests against pension reform. With a strong parliamentary presence but no executive responsibility, the RN and LFI could easily end up in the same charmed position as the M5S and the Lega after the 2013 Italian election. Their constant sniping from outside against the establishment parties translated into victory five years later and a near-death experience for Italy’s government-bond market.

Mélenchon and LFI are instinctive oppositionists but, after two consecutive presidential run-off defeats, the RN may be biddable on some issues since the party wants to show it is capable of governing something bigger than Perpignan. It’s unrealistic to imagine Macron can bathe the Lepénistes’ hands in blood but he could spatter enough their way to disrupt a clean, oppositionist run from the right in 2027.

A political education

I have no idea whether this lucky break has yet dawned on the president. What I do know is that, given how and why Macron broke from the Parti Socialiste (PS) and his political mentors – François Hollande and Jean-Pierre Jouyet – it should.

It’s hard to believe that this time ten years ago, the now re-elected president was just two months into his role as Hollande’s economic adviser and G7/G20 sherpa. Known only to policymakers and their stalkers, Macron was the liberal devil on Hollande’s right shoulder. He was also one of the keepers of Hollande’s biggest political secret (no, not that one): the president who had campaigned from the left always intended to veer right during his (curtailed) decade in power. Hollande’s mistake was to do this at a snail’s pace while keeping left-wing ministers in the cabinet and chucking scraps of red meat – describing finance as his “real adversary” and taxing incomes exceeding €1 million at 75% - to the base.

For a while, Macron too thought this could work and had a reform strategy ready to roll over a left opposition that had no workable alternative. Having introduced the CICE corporate-tax break in early 2013, the government would move swiftly to return the pension system to sustainability with increased individual contributions and a three-year extension to minimum contributory years. Repeated half-measures to address France’s complex, over-large and under-funded pension schemes meant households and businesses were always waiting for the next reform. One big move would stabilise expectations and unleash consumption and investment. At the finance ministry, the focus would switch from closing the deficit with tax increases to reducing spending, especially in local government. At labour, the courts’ involvement in the termination of contracts would be reduced and, just when the unions would think the reform drive was over, the government would table a liberalisation package for the closed professions.

Unfortunately for his adviser, the plan failed to survive first contact with Hollande’s instinct for compromise. Macron and his colleagues worked through the hot summer of 2013 on a big-bang pension reform only to find the president had settled on piecemeal changes after a closed-door meeting with the CFDT union federation. The changes did nothing to simplify more than 40 professional schemes or restore financial equilibrium to the general regime beyond 2020, while the increased contributions were borne largely by employers.

Macron had always been ambitious and lobbied to leave the Élysée for the Valls cabinet as minister of the economy, where he realised his plan to open up (partially) the regulated professions. But it was the pensions episode that convinced him to seek a new coalition outside the PS – bringing together the threads of liberalism and a commitment to the EU from the right and left. It also taught him what he knew already: when it comes to supply-side reforms, speed kills.

As I was saying before I was so rudely interrupted

And it did. From his unbelievably lucky presidential victory and legislative landslide in mid-2017 until his bung to the gilets jaunes in April 2019 then his capitulation to Covid a year later, Macron felt the need for speed. Armed with an assembly majority more like a personality cult, the new president took his own advice and tried to frontload the most unpopular reforms into the first half of his 2017-22 mandate.

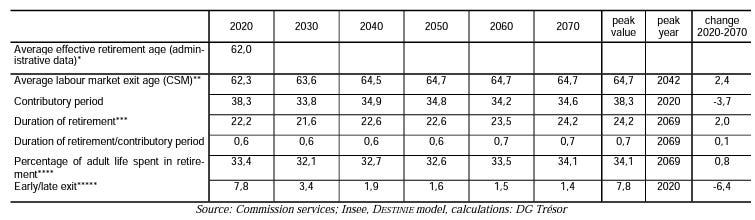

He got two major (and successful) labour reforms under his belt and abolished the wealth tax Hollande had performatively hiked to 75%. Plans to overhaul public finance got sidelined then derailed by the gilets jaunes but it was the pandemic’s despatching of pension reform that most disappointed him and his first prime minister Édouard Philippe. So much so that it became the signature pledge of the 2022 campaign – one that could have kept Mélenchon voters at home for Macron’s run-off against Le Pen. At 15% of GDP, French public spending on pensions is the third highest in the EU – behind only Greece and Italy – with long life expectancy, a low effective retirement age (62) and high annuities compared to final wages. France is also unique in having a patchwork of co-existing professional schemes, some of which allow for extraordinarily early retirement.

He is certain to face resistance from the street but, in the hung assembly, Macron is blessed. He has a clear mandate for reform since he was so upfront about his plans and he has majority support from his Ensemble coalition and from Les Républicains (LR), the centre-right party formed by former president Nicolas Sarkozy. The reform process will be noisy, to say the least, but it will get done despite the alleged “gridlock”.

Equally, if his heart is in it, Macron can rely on LR to start work on reform of the public finances. Since Eurostat started collecting data in 1978, through more than 40 years of booms and busts, no French government has ever run a budget surplus. In the two decades before the pandemic upended the public accounts, administrations of right and left produced an average structural budget deficit – measured as a percentage of potential growth – of more than 2.5% of national output. Public debt was already worth close to 100% of GDP before Covid struck but now it’s close to 115% and will recede only slowly – especially if the economy tips into recession over the coming year.

To narrow the deficit, the typical response of the last four presidents has been to talk about spending reductions but implement tax increases. Without fail, every election campaign over the last 20 years has been marked by a promise from the right and centre to reduce civil-service headcount. In 2017, the right pledged to cut the 5.6-million state payroll by 500,000. This time it was a mere 150,000 but reducing the structural cost of the state is much more complicated than picking a big numerical target, missing it, and assuming everyone has forgotten. Events have made it even more complicated. Thanks to Bashar al-Assad, Vladimir Putin, the coronavirus, street criminals, and Islamic State, the same public that wants lower taxes also wants more border guards, military personnel, healthcare workers, police, and intelligence officers. Fortunately, there are signs – even on the right – of an understanding that public-finance reform requires a rethink of what should be the optimal scope of the state, what can be outsourced and who can be contracted rather than hired. This is the work of years. At the front end of his second term, Macron (once again) has the good luck of governing at a time when public investment – especially in the energy transition and national security – is positively encouraged and the EU’s fiscal rules no longer apply. Instead of following the example of his three predecessors, he should use this opportunity to spend better rather than more. Here again, the shape of the new assembly is on his side, with a built-in Ensemble-LR fiscal coalition - albeit ones that will never be formalised.

Succession

Plenty of LR heavyweights wanted a formal government pact and a realignment of the centre-right but the legislative elections have changed the weather across the political spectrum.

It may sound ludicrous but, a full five years before he leaves office, Macron is already yesterday’s man. The party he built around him in 2017 is no longer his. It’s now three – Renaissance (the movement formerly known as La République En Marche!) in the nebulous centre with 110 deputies, Territoires de Progrès (TDP) on the centre-left with 52 led by ex-PS labour minister Olivier Dussopt, and Philippe’s centre-right Horizons with 27 – all allied to but separate from François Bayrou’s liberal MoDem.

In the six months leading up to the double elections, Philippe was the movement’s dominant figure and France’s most popular politician - a prize he still holds. With even Sarkozy, LR’s founder, dropping hints about a realignment on the right around Horizons and leading LR politicians defecting to Macronie, Philippe was the president’s obvious successor as head of a new grand party of the centre(-right). Today, the future looks less predictable.

LR’s 60-seat tally – while a shadow of François Fillon’s 2007 score – has not only stabilised the party but strengthened its right-wing around Laurent Wauquiez, the former party leader and governor of Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. From now until the primaries for the 2027 election, LR will be absorbed in a constant internal struggle for supremacy between Wauquiez and Xavier Bertrand, governor of Hauts-de-France and figurehead of the party’s liberal faction. The humiliation of the party’s presidential campaign and the surge in second-round switching from LR to the RN has strengthened Wauquiez’s hand. Depending on the RN’s behaviour under Macron II, the chances for convergence of the socially conservative right have never been stronger. The greater the convergence, of course, the more liberal-right defections can be expected from LR to Horizons.

More potentially fascinating is what could and should happen on the centre-left. Although Macron took a chunk of the PS right with him in 2017, the party hung on to a rump of europhile, secularist Social Democrats that was outraged by the formation of the NUPES electoral alliance with Mélenchon. Except for Bernard Cazeneuve, Hollande’s last prime minister, and Claude Bartolone, a former assembly speaker, few were furious enough to quit the party. Carole Delga, governor of Occitanie, ran a slate of PS candidates against NUPES but they all lost.

Why are Mélenchon and LFI a step too far for the PS right when the communists never were? The new left, it turns out, is too eurosceptical, too anti-police, and not be trusted when it comes to secularism or identity politics. After using the NUPES umbrella to hang on to 26 seats, the PS has resumed its independence, but the left has the upper hand. How long can TDP and the PS right resist the obvious? Once TDP has given Macron his pension reform, expect the differentiation within Ensemble to start as Dussopt and especially Clément Beaune, Macron’s European affairs minister, step up their efforts to reunite the europhile centre-left in time for 2027.

More than even Macron, how these emerging centre-left and centre-right politicians perform over the coming five years and how willing they are to cross tribal lines to give the French the left/right programme they want will determine whether voters turn to the extremes in 2027.