"Perfectly Normal Beast. It's a bit like a cow, or rather a bull. Kind of like a buffalo in fact. Large, charging sort of animal."

"So, what's odd about it?"

"Nothing, it's Perfectly Normal."

"I see."

"It's just a bit odd where it comes from."

"Where does it come from?"

"Well, it's not just a matter of where it comes from, it's also where it goes to."

From Mostly Harmless (1992) by Douglas Adams

Like many people who were able to work from home, I shook things up a bit after a month or two of social distancing and with no vaccine in sight.

I Zoomed language classes, cut the carbs, bested personal bests, and only escaped a static bike due to a real-life supply-chain bottleneck. It was podcasting for the New Books Network about Europe, however, that provided the brain gym.

My career as a journalist and analyst has been devoted to understanding and predicting (preferably accurately) the politics and policies of the EU. But it’s been learning by doing. My knowledge has been grubbily practical – not as a hands-on practitioner, mind, but at one remove - asking annoying questions. Don’t misunderstand me; going all the way back to the Maastricht treaty negotiations, I’ve studied draft treaties, directives, regulations, policy papers and think-tank pamphlets. I’ve even performed the surreal task of reading non-papers. But, until 2020, I’d read no political theory since wasting large parts of my early twenties on the treacly prose of Louis Althusser and Nicos Poulantzas - cursed be their names.

This podcast series changed all that, and I’ve read more serious books in the last two years than I did in the previous 15 and more on theoretical inquiries into European integration than … well … ever. It turns out there is a rich academic literature attempting to answer the questions I’ve been asking myself for 30 years: What exactly is this strange beast we call the EU – this part-state, part-club? Does it have any true precedents? Are its federal ambitions genuine or hot air and, more to the point, are they even necessary? Is the bicycle metaphor1 apt or just a Sciences Po cliché? Can’t we learn to love the EU just the way it is?

A few books helped me get to grips with this. Two of them are critical histories: Mark Gilbert’s European Integration and Kiran Klaus Patel’s Project Europe stand out for their aversion to euro-Whiggery. Gilbert, who has a page-turning narrative style, reclaims traditional villains Charles De Gaulle and Margaret Thatcher as simply having alternative intergovernmental visions of integration. Patel reintroduces the notion of the Communities as just one model among many post-war associations – one that proved the most evolutionarily fit but embedded the "disintegration and dysfunctionality" that has come to haunt policymakers in their design.

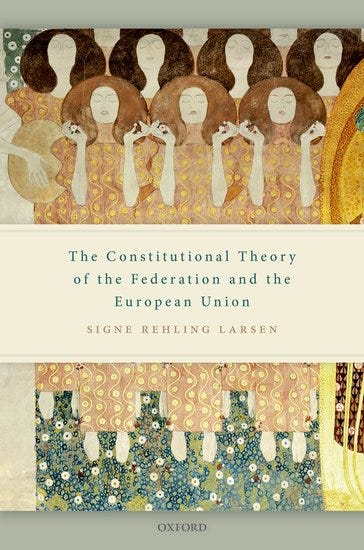

Histories, even critical ones, only get you so far in taxonomizing the EU. For that, you need a political-science framework. As a French diplomat is once reported to have said (apocryphally, I’m sad to say): “That’s fine in practice, but will it work in theory?” For me - and this is always going to be personal - the two books that have come closest to theorising the EU that I know are Štefan Auer’s European Disunion: Sovereignty and the Politics of Emergency and Signe Rehling Larsen’s The Constitutional Theory of the Federation and the European Union.

Cometh the Auer

Occasionally, a euro-book finds its moment and escapes academia's confines and eye-watering pricing. In 2013, Ulrich Beck’s German Europe captured the backlash against Berlin's newfound assertiveness during the sovereign-debt crisis. After the refugee crisis and Brexit referendum in 2015-16, Ivan Krastev’s After Europe warned of disintegration as nationalism appeared to be trumping globalist liberalism, and Patel’s Project Europe questioned the union's foundational myths.

Although it was written before the 24 February invasion of Ukraine, European Disunion identifies the EU's structural frailties, especially when set against an aggressive and self-confident Russia. Like Patel, Auer argues that the union's weakness is its point. Designed to disperse power, contain popular democracy, and project influence abroad only through its power of attraction, the EU's hybrid form – falling somewhere between a multinational state and a multilateral organisation – comes closest to the ideals of Germany. Built only for the good times, the EU's bid to bypass politics makes it brittle and fumbling in an emergency - and there have been plenty of these since 2008. It has improvised its way through successive crises – over public debt, migrant surges, the withdrawal of a member state, a pandemic, and a major border war – but lurching between pettifogging legalism and emergency rule cannot continue. "Europeans do not have the luxury of living in a politics-less world," he warns.

A Slovak teaching in Hong Kong, Auer is especially harsh on Germany, the EU’s exemplar state, for a political cravenness that fails to qualify even for soft-power status. Successive governments – mostly under Angela Merkel – have chosen to increase their energy dependence on Russia, handed leverage to Turkish (and Belarusian) strongmen by subcontracting migration control, and left the rescue of the euro to the European Central Bank. Rome and Madrid make a point of tucking into Berlin’s slipstream while the French confine their power projection to Africa and use their influence in Europe to act as a Moscow-Washington mediator.

Until now, the tendency of the EU and its member states to behave like a Big Switzerland has been irritating. When Ukrainians started dying for the blue-and-gold flag – and remember, this started not this February but in February 2014 during the Euro-Maidan revolution – it became shaming. As deputies applauded the arrival of the 12-star flag in the Ukrainian parliament last week, all I could think of was Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s fury at its presence in the national assembly and beneath the Arc de Triomphe. No one was supposed to take the EU and its star-spangled banner seriously but its eastern aspirants did. Yet, as Auer points out, until the invasion, the EU's offer to the population in its giant eastern neighbour remained destructively half-hearted - “not quite enough for Ukraine but too much for Russia”. It took Vladimir Putin's colossal miscalculation and the swift emergence of an intra-EU borderland lobby to impose a rethink on Berlin, Paris and Brussels. The result is formal candidate status for Ukraine and Moldova although, frankly, this is a holding position as the EU works through the principles then the practicalities of a halfway house for the lengthening queue to its east.

Auer makes a nice point that “challenging the EU’s economic orthodoxy can prove to be more costly for the political survival of its leaders than openly ‘illiberal’ rebellions from member states”. Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán consistently violates the EU's values and norms (the union’s implicit constitution), receives no tangible punishment, and is rewarded with a fourth consecutive term. By contrast, Alexis Tsipras, Greece's former premier, challenged the previous government’s economic adjustment programme and debt-repayment agreement, and was forced to take a third that led to his subsequent electoral defeat.

Although this is a fair criticism of EU prioritisation and perverse incentives, I think it’s an apples-and-oranges comparison in practical terms. The 2015 leg of the six-year Greek crisis had to be settled rapidly because both sides were operating in market time and Tsipras' official creditors - not just Germans but poorer Slovaks and Balts - were never going to provide debt forgiveness in return for no meaningful policy conditions (Yanis Varoufakis' position). On the other hand, Orbán's makeover of Hungary into a "partly free" democracy has been conducted in slow, political time with no market discipline. Treatment should be identical but that will require a sanction equivalent to default or expulsion – a proposal Auer opposes as unfair to Hungary’s large liberal, europhile minority. Of course, the same could be said for the UK’s 16 million Remain voters.

Auer restores the nation state as the locus of power in the EU. But, in my view, like many frustrated with the performative federalism of many politicians as they make the EU an excuse for their own inaction, he understates how integrated these nations are as members. Yes, real power lies with the Council of Ministers and the big states, but the EU is no UN or WTO. Its law has primacy while trade, competition, subsidy, agricultural and fisheries policies are essentially federalised among 27 and monetary policy among 19 members.

Back to basics

There is nothing quite like the EU. So, is it unique (sui generis as the literature likes to put it)? I’d come to think so until I read Signe Larsen's revelatory book, which has failed as yet to achieve escape velocity from the pull of academic pricing even for the Kindle version. So, get a library order in. The EU may be unique today, Larsen argues, but historically it isn’t. “The categories of the state have blinded us to federalism. We have forgotten the federation as a political form”.

I'd like to claim I'd forgotten it too, but the truth is, until I read the book, I hadn't grasped the difference between a federation and a federal state. Plus, I’d also only ever thought of the founding six member states as nations and not (with the exception of Luxembourg), as Larsen reminds us, as “metropoles of imperial unions” in search of large substitute markets. “When their empires started to collapse, they became member states of a federal union”.

Start here and the design and evolution of the EU look rather different. “The autarkic European nation-state, if it ever existed, was the exception rather than the rule,” she writes. “Nevertheless, it is the myth of the self-sufficient nation-state that lies at the heart of much scholarship on post-World War 2 European integration. Instead of interpreting the EU in line with previous projects of market creation through empire and federation, the story of the post-World War 2 project of European integration is often interpreted as a ‘conflict’ or ‘competition’ between the Union and the Member States as the dominant forces in a zero-sum game”.

By removing the nation state as a template for the EU, its true ancestors – the US before the civil war and Germany’s 19th-century confederations – come into view. “The federation is a discrete form of political association with its own legal and political theory that cannot be understood on the basis of the theory of the state”.

It may not satisfy its aspiring federalists but it turns out the EU is a perfectly normal federation, just not a federal state. Where Larsen finds the EU to be distinct from the Swiss and German confederations is in its willingness to expand. So far only the US has proved to be a more ambitiously expansive federation while the EU is easily the most constitutionally diverse with five monarchies and four executive presidencies.

Belonging to the federation changes the nature of the nation state. They lose the monopoly of public power within their own territories and over their populations. Free movement allows citizens to escape their own states and, even if they don’t, their relationship with government is fundamentally changed by belonging equally to another constitutional order they can call on for protection against their own and other states in the federation.

Of course, this works both ways. The EU is also defined by its “lack of a monopoly on the use of public power” and its institutions’ competences are limited to specified fields where EU law has supremacy. While the union has independent bodies – the European Commission, the ECB and the Court of Justice – with cross-border powers, they have no prerogative or authority to establish their own aims.

The Communities and the union evolved in contradistinction to the pre-war dictatorships that were perceived to have grown out of an excess of democracy. Permanent institutions and overriding norms that floated above politics were built into the German constitution and into ambitions for the EU as a second failsafe. While this has worked well for Germany and southern states that emerged from dictatorships, it has stoked up problems in the British, Swedish and Danish “evolutionary democracies” and with the new eastern states where communism is regarded as something imposed from the outside.

In common with Auer, Larsen detects danger in the EU’s increasingly frequent resort to emergency rule. She warns: “This is particularly dangerous for the federation because it introduces a strong unitary element of reason of state that threatens the dual political nature of the federation”.

Here the books converge. Auer centralises the nation state and Larsen the federation but both see emergency improvisation as a ticking bomb for the union.

The notion that, like a push-bike, European integration must always be advancing or it will fall over.