Spoiler: it doesn’t. Yet, with his five-word cartoon version of the Great Man theory of history, Michael Heseltine has captured an important truth. The comical downfall of Boris Johnson does at least mark the end of Brexit’s performative stage – three years of farce following three years of tragedy.

As long as Liz Truss and Suella Braverman are eliminated early on in the now-routine vote by 150,000 English pensioners for the UK’s head of government, the next prime minister should be an administrator rather than a Brexit culture warrior.

Love them or hate them – and I can guess which side of “or” most of you fall – Rishi Sunak, Penny Mordaunt, Sajid Javid, Tom Tugendhat, Nadhim Zahawi, and Jeremy Hunt are at least organised and serious politicians with combs instead of balloons (not Javid, obviously) and policy goals.

Johnson was never that. Yes, I too am one of the many journalists who knew him when he was a budding fiction-writer and coffee-ponce back in early-90s Brussels. But our stories of Poundshop Sebastian Flyte are as nothing to those from government like Rory Stewart on his diplomatic dilettantism or Claire O'Neill on his admission to never understanding climate-change policy. Most importantly, since it brought him to power and did the greatest national damage, there is Dominic Cummings’ LOLz confirmation that Johnson “never had a scoobydoo” what Brexit involved.

He didn’t need to. Johnson was only ever a Brexit delivery mechanism for Cummings and the Conservatives’ European Research Group (ERG). Once Brexit was delivered, things had to fall apart since the coalition agreed on nothing except the need to leave. Free from the EUSSR’s state-aid shackles, Cummings had a cunning Gaullist plan to nurture a thousand Bull Computers – winners he, the Haut-commissaire au Plan, would pick to lead the world in biotech and artificial intelligence. The new Red Wall MPs are simpler folk. They just want to redirect existing public spending out of London and into Danelaw.

As for the ERG’s militants, they quickly lost interest in Brexit and switched their ire to vaccine and mask mandates, wokery and Johnson’s net-zero policies. For them, Brexit was only ever a means to an end: a return to and extension of the Thatcher revolution. They could have done this inside the EU but there was no telling them. With Johnson’s removal, Steve Baker and friends see an opportunity to resume the work of reducing public spending as a percentage of national output, cutting taxes, extending (some) social freedoms, and calling time on the energy transition. The one Johnsonian legacy they would keep is his and Truss’s brinkmanship with the EU over the Northern Ireland protocol.

Fortunately for everyone except the Labour Party, Johnson’s Trump-like behaviour during his last days in office means Conservative MPs are likely to opt for a low-risk choice with a reputation for competence and reading briefs. That means one 2016 Remainer – the likes of Javid, Tugendhat, or Hunt – running off against a 2016 Leaver – Sunak, Mordaunt, and Zahawi. As ballots progress, expect strategic swaps to ensure Truss and Braverman never make it to the final two.

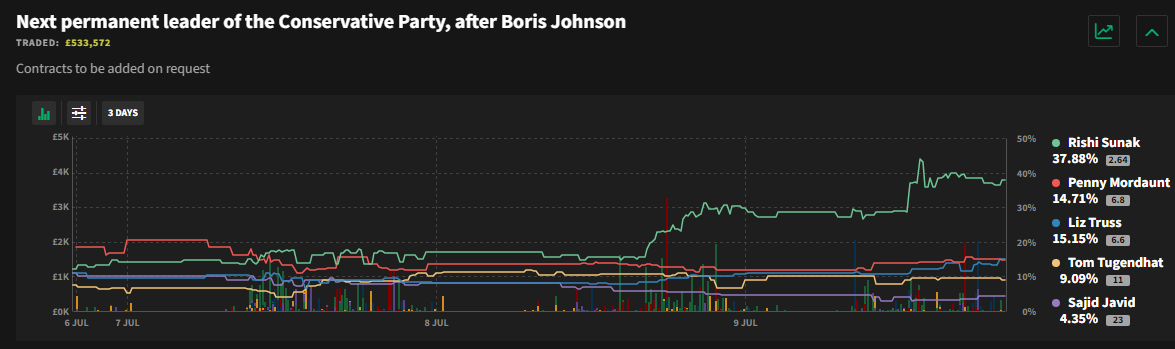

Implied probability of victory from matched bets on the Smarkets exchange - 9/7/2022 20:00 BST

Don’t you dare

Against this backdrop of Tory disarray and surging support for the opposition, why has Keir Starmer chosen to scale back Labour’s European ambitions to just “Make Brexit Work”? Among ex-Remainers, I was probably one of the few who was not disappointed by Starmer’s announcement that the next government will not seek to rejoin the European Economic Area (EEA) or negotiate a customs union with the EU.

I wasn’t disappointed because Rachel Reeves, Starmer’s powerful shadow chancellor, had said the same thing in January. Worse, actually. Asked whether she could see the UK re-joining the EU or EEA in the next 50 years, she replied: “No, I can’t see those circumstances”.

Well, I can, and within 10 years. And, while I would prefer Labour to adopt the new Liberal Democrat roadmap to the EEA, I can understand Starmer’s repositioning. Just by being in government, Labour and the Lib Dems will repair some of the worst damage to UK-EU relations and solidify Northern Ireland’s special status in both markets. Re-joining popular EU programmes like Horizon Europe and Erasmus+ and agreements on veterinary standards for agri-products, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, mobility for short visits and entertainers’ tours, and post-Ukraine security will represent a significant Reset for both sides.

And remember, as I said in my first 24/2 post (The politics of gravity), this search for a new political and economic relationship short of the EEA will be going on at the same time as the EU is exploring a halfway-house option for Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia and at least some of the western Balkan states. Europe is set to transform during Starmer’s 2024-29 term and other options could well pop up. Above all, a non-Tory government needs to democratise and broaden the EEA before readmission. Starmer doesn’t need to play all his cards now.

Frankly, I doubt this is the Labour leadership’s reasoning, which is more likely to be partly defensive and partly delusional. First, the defensive. Yes, public opinion appears to be shifting against Brexit. YouGov asked people on 6-7 July whether “in hindsight” it was right or wrong to leave the EU and wrong led right by 13 points, and was ahead among all age groups below 65 and across all regions.

The problem, as Labour’s pollsters point out to them, is that the core Leave vote is still solid and evenly distributed across England and Wales while the Remain vote is concentrated. The Lib Dems, Scottish National Party and Greens are all well-placed to win Remain-voting constituencies but Labour needs both to hold its Remain seats and regain its Leave districts in the North, Midlands and Wales. Here again, Reeves – who represents a Leave-voting seat in Leeds – said the quiet part out loud in her January interview. “I don’t want to go back to a system of free movement,” she said. “It was the biggest reason people voted to leave and I don’t want to go back to that model”.

Picture now the Tories’ arms-length, Moscow-aided election campaign if Labour even hinted at a return to the EEA and free movement in their first term:

Camden Keir wants to overturn the heartland’s democratic choice from 2016.

Free movement was bad enough then with 85 million Turks coming to take your jobs and housing and fill up A&E but it will soon be 45 million Ukrainians and three million Moldovans with their 250,000 (nudge nudge wink wink) Roma.

Non-EU single market members have to “pay billions to Brussels” with no vote!

The single market is a stepping stone back to the EU and the end of the pound.

It would take a 1992-vintage Bill Clinton, 1997 Tony Blair or 2017 Emmanuel Macron to resist that onslaught. Starmer is a clever man and, on his day, a skilled parliamentary performer but he’s no Bill Clinton. I wouldn’t trust him or his front bench to win that campaign. And win he must.

Worse than you think

In his 2001 party conference speech, Blair told a story: “Just after the election, an old colleague of mine said: ‘Come on Tony, now we've won again, can't we drop all this New Labour and do what we believe in?’ I said: ‘It's worse than you think. I really do believe in it’.”

I have the same nasty feeling about Starmer’s retreat. I’d like to believe that lack of self-belief was Labour’s main reason for shying off the EEA. However, I fear they may share the same delusion as Joe Biden and the Democrats when they took power in January 2021: that we should all move on from the political crisis that just happened and deliver instead on “kitchen table” policies for working-class voters. In the US, that meant a massive public-spending package, with infrastructure dollars and child tax credits heading disproportionately to Republican states where voters pocketed the cash, stuck to their culture war, and blamed the Democrats for wasting money on their neighbours. While much smaller in cash terms, Labour’s plans are far more ambitious in scope but just as politically fruitless.

Instead of wasting time over a six-year culture war or reviving Corbynista demand-side policies, Starmer and Reeves propose a “modern supply-side” programme to recoup a decade of suboptimal growth by raising productivity. And, in a hat-tip to Gordon Brown, the king of bipartisan commissions, Reeves has set up an expert committee chaired by Jim O’Neill, a former Goldman Sachs chief economist, to solve the productivity puzzle. This was beyond the wit of government before the shock of leaving the EEA so good luck to them.

Since Starmer has accepted Brexit constraints until at least the end of the decade, some are advising him to move off the defensive. From the left, James Meadway – John McDonnell’s advisor when he was shadow chancellor, which tells you a lot – calls on Labour to use the space afforded by “great economic reformer” Johnson to “use its expanded government powers to support favoured industries”. From the right, only this week, William Hague implores Starmer to come up with “an energetic plan for the future that makes the most of our national advantages”. This was a lovely idea until it came to the detail: more task forces and, that old Brexiteer favourite, unpicking the Solvency II directive to incentivise investment in smaller, more innovative and higher-risk companies and infrastructure projects.

That brings us to the third big (but little noticed) Brexit event of the week after Johnson’s fall and Starmer’s tactical retreat. For years, the better-informed Brexiteers have identified Solvency II’s so-called matching-adjustment rules as an impediment to infrastructure investment. This is because they balance long-term investments with long-term liabilities and provide an incentive for insurance companies to allocate most assets to investment-grade bonds. Outside the EU, Brexiteers always claimed, loosening this match would be easy and release £100 billion for higher-risk investment. It turns out, however, that the British regulator – the Prudential Regulation Authority – shares the concerns codified in the directive. Why wouldn’t they? Every directive was co-drafted with the British. In a speech last week, PRA chief executive Sam Woods warned that “less capital, fewer checks and fewer restrictions on assets … means more risk for pensioners and other policyholders”.

Brexit meets the real world episode 50. This is how the tragedy and farce of the post-2016 years will end. Bit by bit, reality check by reality check, and as Europe, the US and Russia regroup and rebuild.

“Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Winston Churchill, an actual Great Man, 10 November 1942.

For next BJ article:

“When Boris comes, England goes”